Truly Heartbreaking

National Celebration

by Sheridan Morley

The Spectator

This has not perhaps been the greatest of weeks for Andrew Lloyd Webber, who last month became the first-ever British theatrical composer to make it to the House of Lords; Gilbert, Sullivan and Coward had to make do with mere knight-hoods, while Novello never even got that, largely because of an unfortunate wartime prison sentence for petrol abuse, which in those days meant not sniffing it but using more of it than 1944 regulations permitted.

Not only has Lord Lloyd Webber had to put the road-closed notices up on his Sunset Boulevard here and on Broadway, but he also faces a $6 million lawsuit from a New York theater-goer who alleges that she was 'assaulted and abused' by one of his dancing Cats. Added to all of that, he has also just decided not to transfer his latest musical Whistle Down The Wind, form Washington to Broadway in the spring as previously announced.

There is a kind of logic in this, though it is not the logic you might expect: Whistle Down The Wind is not too bad for Broadway, it is, if anything, rather too good. His lordship's latest musical is little short of a miracle, which in a way is what it is all about. The show started from a novel by Mary Hayley Bell, written 40 years ago and subsequently made into a film with her daughter Hayley Mills and Alan Bates; it concerns, very simply, three young and alienated children from what would now be known as a dysfunctional family who, in a barn, come across a runaway killer with bleeding hands and feet. The runaway's first words on being discovered by the kids are 'Jesus Christ' and that, it being almost Christmas anyway, is who they take him for, complete with wounds of the Crucifixion.

The Washington opening at the National Theater was the first time that Lloyd Webber had given a premiere of a score in American since Jesus Christ Superstar all of 25 years ago, but when Whistle Down The Wind completes its sold-out season there this month the show will be taken back to the drawing-board, possibly to reappear on this side of the Atlantic in a rather smaller theater. Unsurprisingly, given a shamefully cool Washington reception, the creators of Whistle (Lloyd Webber, director Hal Prince and lyricist Jim Steinman) seem to have decided this week that theirs is not, at $75 a top ticket, what is now meant by a Broadway hit and in this they could well be right.

But, as with Aspects Of Love, the very best Lloyd Webber is often to be found in his least popular or populist shows, and given the right-priced, right-sized London theater, I believe this one could run if not forever than at least for half a decade or more. Any worries that Hal Prince might have over-balanced a fragile fable with a scenery-heavy production, or that Jim Steinman's day job as Meat Loaf's official songwriter might somehow have got in the way of this classic are immediately dispelled by the opening scene.

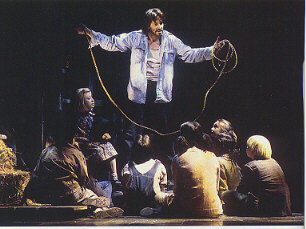

The location has been moved from Yorkshire to Louisiana in the early 1950's; we are in a clapboard community of losers and drifters trying to survive in a small backwoods town where even the train (one of Prince's most brilliant scenic effects on Andrew Jackness's wonderful set) never bothers to stop. And this is still the bible belt, where snake-charmers and Elmer Gantrys and young wannabee James Deans co-exist in an uneasy, incestuous disharmony.

Webber's music perfectly matches the mood of Steinman's acutely and achingly brilliant period lyrics; this is a score redolent of love and loss, of death and redemption, and one of the most truly heartbreaking I have ever heard. But there remains the perception problem. The truth is that this is not the lush, romantic Lloyd Webber that America has taken for granted since Phantom; instead it's a nervy, edgy show of infinite courage about the nature of faith, whether instinctive or imposed. Despite the change of setting it remains utterly faithful to Mary Hayley Bell's original, and a largely unknown cast do it proud.

The title song and one or two others ('Nature Of The Beast' and 'When Children Rule The World') will one day be recognized as among the most hauntingly beautiful and chilling that Webber has written, but there is no escaping the fact that this is a down-beat show of considerable danger, intelligence and cynicism, none of them assets when you try to sell the CD or satisfy a Broadway matinee of matrons still awaiting the return of Michael Crawford and Sarah Brightman.

Trevor Nunn, as he starts his National Theater regime, could do a lot worse than give the British premiere of Whistle Down The Wind at the Cottosloe next year; it badly needs a classical background of that sort, and a cast who would be at home in John Steinbeck or William Faulkner. For this tremendously theatrical, evocative masterpiece must not be allowed to vanish, simply because it is not sufficiently commercial for a theater dominated by tourists and out-of-towners in search of a celebration.