‘Tra-La-Tra-La-Tra-La’

Flowers that Bloom in the Spring

by Jim Steinman '69

Amherst Student

A powerfully honest, though perhaps overly "muted" performance of "The Madness of Lady Bright" will be presented again Tuesday night at Stone Theatre at 8:30. The play was first performed at Stone on Friday and Sunday.

Lanford Wilson's brief, sparse and economical one-acter displays, in almost monologue form, an aging queen, Leslie Bright, as he/she flamboyantly propels herself through what might be merely one of many "little" nervous breakdowns that strain her "hot, lonely, faggot" room. Two other characters, a boy and girl, add counterpoint to Leslie's words sometimes, acting the role of a perverse mocking chorus, and often stepping into the action, supplying memories and motions to supplement Lady Bright's ranting fantasies and reminiscences. But the play is still one person, one mind. It is a look at a queen, not a "dissection" or analysis, but a "look."

This is by far the most impressive aspect of the script: its cool, objective style, a rare thing in plays about queers. There is no attempt at plastic moralizing, such as is often found in the work of "straight" writers, imagining from a condescending, patronizing distance the "sad little world of the homosexual" and then trying to humanly mourn for that world with affected, trite plays bleached with Lestoil tears.

And Wilson does not indulge in soft easy sentimentality. There have been a number of "poetic, self-conscious" Tennessee Williams imitation "epics" that wistfully present fags as martyred victims, tortured saints, extra-sensitive angels, or holy demons, towering above the rest of common humanity with their watery blue superiority. These works seem like nothing more than wish-fulfillment for the authors. And often there is distant hiding from the truth, as in the numerous works of Albee, Williams and disciples who write about queen but disguise them as heteros, producing the confusing impression of watching fags play straights play fags. And certainly Wilson doesn't proselytize. He has nothing to do with a school of drama, represented best by New York's "Theatre of the Ridiculous" which tries with outrageous and amazing perverseness to portray all heteros as weak vegetables and all homos as living wild ecstatic orgiastic lives with a cock in every pot. One recent extravaganza, "Gorilla Queen:' portrayed the story of a swishing "Queen Kong," a huge ape who reaches cosmic consummation while being reamed by the antenna of the Empire State Building.

But Wilson belongs to none of these "schools" of fag drama. He is a traditionalist; his work is naturalistic and unhysterical, most refreshing for its untampered job of plain reporting.

Wilson is helped in his detached style by the fact that Lady Bright does much of the writing herself. Queens self-dramatize, they create themselves, turn themselves into monstrously exaggerated tragi-comic vaudevilles. Therefore, Lady Bright exposes herself without Wilson resorting to pushy, contrived probing. The queen lays it on the lines for all to see.

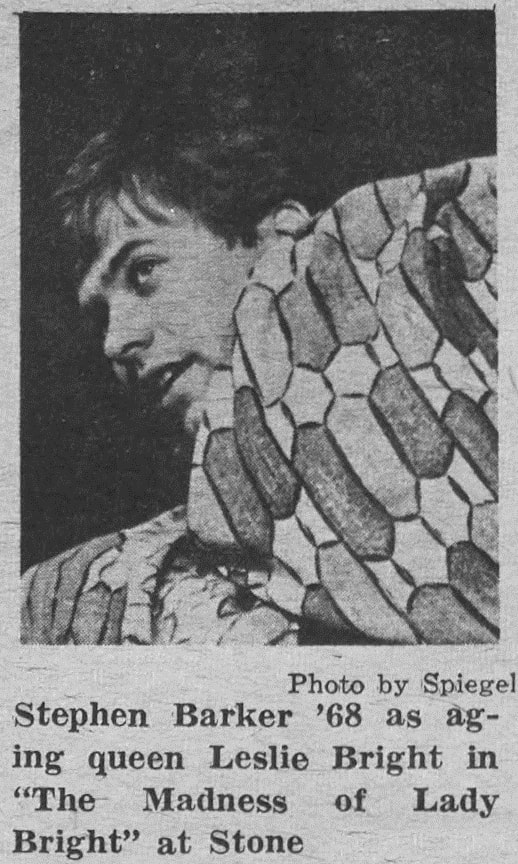

If there was a flaw with the Stone production, directed by Barry Keating '69, and starring Stephen Barker '68 as Lady Bright, it was that this "self dramatizing" element wasn't sharp or grotesque enough. Barker did an amazing job, some of the most memorable acting by a student in recent plays here, but I felt he was too soft, too restrained. I kept wanting him to "breakout" more. I think the part needed more nightmarishly large exhibitionism, more brittle harshness. This was a very gentle queen, in movement and speech, and therefore her self-deprecating remarks were neither as bitterly sad or caustically funny as they should be. And as a result of this loss of "hardness," the breakdown itself seemed too sudden and heavy, and the constant self-pitying was too sentimental and not bleak enough. At the end, one felt wistfully sad — poor queer. I think you should feel empty, smothered, and in the presence of pure despair, not pathetic desperation.

Also, the character was not convincing as a fully realized human figure simply because one could just never believe that this "Lady Bright" ever took it in the ass. I don't know a better way to state it. Maybe this can't be helped, but I never really believed the sexual drive or orientation of Leslie. He seemed too womanish, too feminine. Lady Bright is a prancing caricature of a female, this ote too often simply and very convincingly was a female, and a pleasant one too. At times, as she/he bemoaned her aging, you could have been listening to any woman in menopause. The extra level of grotesque "parody" was gone and same dramatic tension missed. Despite these qualifications, the ending was still intensely moving, and blackly drained.

Keating's direction most of the time was properly inconspicuous and appropriate. Whenever one sensed the director's hand in creating a stylized dramatic effect, it was never intrusive. Every "device" worked beautifully. And it is the best praise I could possibly give to everyone connected with this play that never once was an attempt made to cheapen it or get easy laughs our sympathy from an audience. Obviously, each person had worked with a great deal of integrity and concern to produce an honest production, not a showy product. This represents the best sort of work student drama can present.

Stephen Collins '69 and Beth Joplins were fine as the boy and girl and the sound was used excellently. I thought the set was too little-girlish and prissy. It should have been harsher, more dramatic, and the use of pink and white crape paper was especially poor : really tasteless.

Frank Hight and Mike Garrett performed another perversely hilarious "move," with superb musical background.

Source: Amherst Student archives