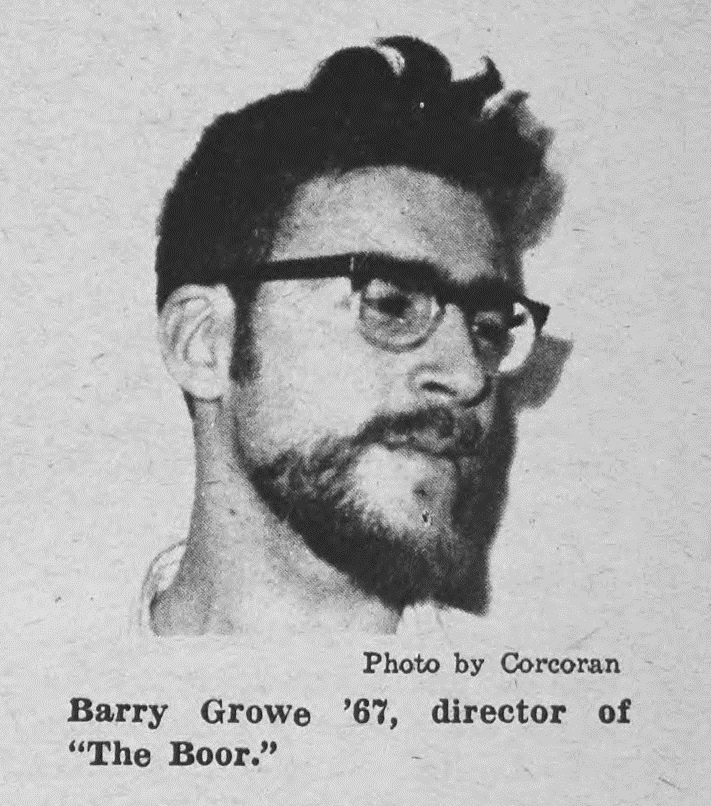

THE BOOR, by Anton Chekhov. Directed by Barry Growe '67 and designed by Andrew Eustis '69

by Jim Steinman '69

Amherst Student

The second of the one-act plays was Chekhov's "The Boor," directed by Barry Growe. Everyone involved did a nice job. It's a nice play. Thin, predictable, unsurprisingly, mildly funny. I can never quite understand why so many fervent admirers try to think of many of Chekhov's one-act comedies in the same light as his full-length masterpieces. Specifically, the two one-acts by Chekhov that I've seen here. "The Marriage Proposal" and "The Boor" have both left me completely unmoved. Either too much laughter, or any other significant response. I still see them as very good skits. Fine for television. As for the theatre – well, they're nice, and certainly not challenging, for the audience especially. We sit and watch, and when we see a little funny part arrive, we pick up our cue and pleasantly laugh. And when it's over, we forget it. Even before it's over.

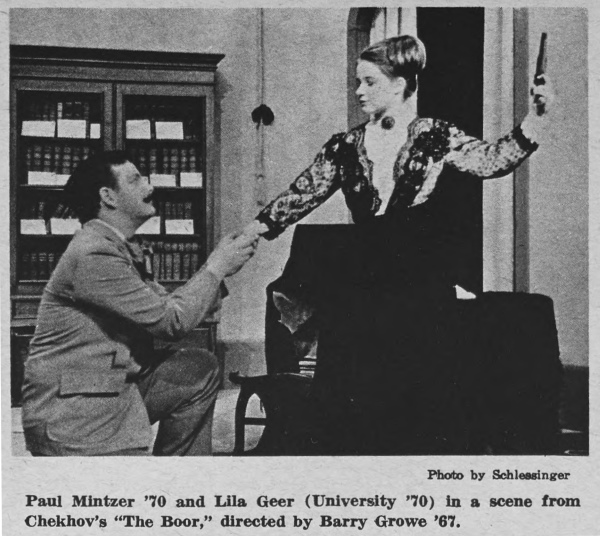

Anyway, down at Kirby, Chekhov was handled with obvious care. Paul Mintzer '70 played Grigori, the retired military man who comes to a widow's house to collect a debt, argues with her, challenges her to a duel, and by the end, realizes he's in love with her. We realize it by the middle. Or before. Mintzer did a fine, re-strained job. Somehow he resisted being Jackie Gleason. All to the benefit of the play, too.

Lila Geer (University '70) as the widow was competent, but she missed most of the comic potential of the part. There was too much restraint to no purpose, without transition or variety. The result was a bit pallid, un-authoritative, underdeveloped. Growe handled tne movements and the slapstick with admirable timing and fluidity, though at times he seemed uncertain of whether to try for completely mad, over physically oriented comedy or a more underplayed, suggestive, casual form of "ensemble wit." Overall, he did a good job of keeping the whole thing moving forward, anyway. And the faster this one moves, the better. For my taste, at least. George Bentley '70, in the other role of the old butler, was funny and believable. Both he and Mintzer also seemed to be enjoying themselves tremendously. So did the audience. As the play ended, and the actors arranged them-selves for a rather unnecessary, self-consciously "cute" curtain call that almost summarized the tone of the production, I could hear multitudes of little old ladies around me chittering to no one and everyone in particular: "What an adorable little work." They were very nice ladies, too. Even without tennis sneakers. In fact, some of them were men, and students from Smith and Amherst. Maybe next year we'll all get together again over muffins and tea and a nice safe play.